New book by Medicine alumnus recounts his work in a Somali war zone

John Tomlinson graduated from Liverpool in 1980 and went on to forge an exciting career in Public Health, including setting up and running a hospital in Somalia, his harrowing and humorous experience of which is shared in his new book, Noises After Dark.

What brought you to Medicine, and to Liverpool?

Biology, and especially human biology, was my passion at school. However, no one in my family had ever been to university, and so I was not sure what I wanted to do should I ever get there but knew I wanted to make a difference in some way.

I was always impressed with the family GP and how doctors make such a difference to people’s lives and I developed a real interest in all things medical in the news and on TV. My biology teacher was really supportive and encouraged me to dream.

I was not successful with my first round of applications and despite having good grades returned to school to improve them further. A new inspirational head teacher encouraged me to write a letter to as many medical schools as possible to enquire if they would consider me the following year. Liverpool promptly invited me for an interview, at which I was offered one of three remaining vacancies.

I will always remember the admission officer’s words. ‘What we want is someone who is committed and willing to work hard, it’s a tough job with all the long hours. So, if you are willing to go back to school with your grades and spend another year trying to get here, then that says something about you young man. I say let’s have you now and save you a year.’

So, it was not so much ‘me choosing Liverpool’, as ‘Liverpool choosing me’. It was meant to be and that moment was to change my life.

What do you remember of your first days and weeks as a student doctor?

When I started university I had no idea what to expect. The halls of residence were full, so I was placed with a local family on Menlove Avenue I was treated as part of the family, even now they still send me a Christmas card every year! Liverpool became my second home. I discovered that it had, and still has, a real sense of community, with friendly people who are very proud of their city.

It was fantastic to mix with so many people from so many different backgrounds.

One student was an ex-merchant seaman. When I asked why medicine at this stage in his life, he smiled and replied that the ship’s doctor was so awful he thought he could do a better job!

A number of lectures and evening meetings of the Medical Student Society were still given in the atmospheric Victorian lecture theatres full of old dark wooden benches that were arranged like terracing up a steep hillside. You definitely had a feeling of stepping back in time.

The weekly anatomy sessions on real cadavers were unforgettable. No amount of washing could remove the smell of formaldehyde. It was the 1970s so many students had long hair, and tying it up was essential during dissection if you didn’t want it impregnated with formaldehyde conditioner!

John with friends on campus

John with friends on campus

What has stuck with you most from your time at University?

The daily rush. During clinical placements you had daily morning lectures, after which you would race to whichever hospital you were based at. There were many smaller hospitals that eventually closed to be merged into the new Royal Infirmary. This included the sailor’s sexual health clinic in the docks. Only in a city with such a famous sense of humour could the clinic be so aptly named ‘The Seamen Clinic’.

‘The Friday Circus’ as it was called was hugely entertaining for those watching, but a ritual humiliation for those taking part. A small number of final year students were selected in turn each week, and everyone knew that one day it would be them standing on stage. The students were given a clinical case and had approximately one hour to find their patient, take a history, perform an appropriate examination and write the case up before returning to present their patient to a panel.

The auditorium was normally packed and had the atmosphere of a sporting event. Any student from any year who wanted to observe was able to attend, often with standing room only. The panel were deliberately difficult, as this was regarded as a toughening up process for the final exams, which were never as bad!

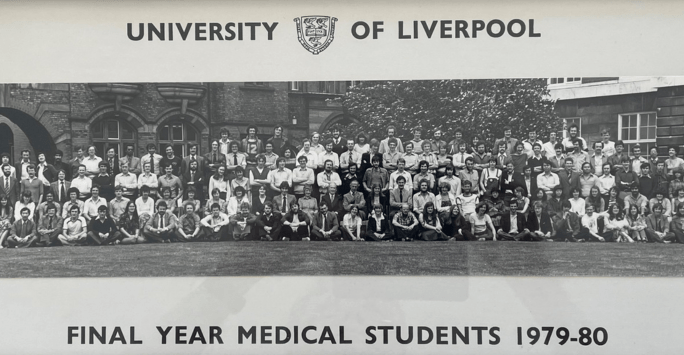

The Class of 1980

The Class of 1980

How did you overcome any challenges you faced at University?

When I first started I was a quiet and shy person. The regular interaction with patients on clinical placement was a huge help here and made me very comfortable having everyday encounters with complete strangers.

I failed my first exam in my first year. It was an MCQ with negative marking for incorrect answers. I had stern feedback from my personal tutor - the first and last time I ever met him. I quickly learned not to guess!

I think the main issue with studying medicine was, and still is, the sheer volume of material to learn, including all the medical terminology, which they say is equivalent to learning a new language.

I do not remember being taught any specific study skills back then, and it was very much about picking ideas up as you went along - taking summary notes at speed and developing short hand if you could, underlining in textbooks, making your own memorable acronyms, holding spontaneous quizzes with your friends and flat mates. Thankfully this has changed, and I feel students are now much better prepared.

How did your studies and placements help you decide on your path through medicine?

We were able to sample virtually every specialty, even if only for a short time. There were certain clinical placements that made me think more broadly, such as a research project into Health and Housing during a primary care attachment.

One of the most important influences on career choices was that of really inspiring consultants and GPs, just like any good teacher at school.

Working with a consultant from Barbados and a junior doctor who had worked in Montserrat was what originally made me think about working overseas - which was to become an important part of my career.

Looking back, what skills did you develop that have been useful in your practice?

Really good interpersonal skills - being able to put patients at ease, explaining clearly using language they understand, and examining patients appropriately to avoid any embarrassment.

I recognised the importance of having a sense of humour, even in difficult times, with staff and patients.

The Liverpool sense of humour is of course famous and I do miss it. I remember virtually every hospital porter being a comedian and able to put patients at ease so quickly.

Reflection, reflection, reflection. Being able to reflect on your own and others practice, and accepting constructive feedback, is very important. This is now part of professional revalidation, but not then.

Where did you begin your clinical practice and what did you go on to from there?

My house jobs, now Foundation Year One or FY1, were in Walton Hospital, followed by a continuation of general medicine at a SHO (FY2) post in Bangor North Wales.

I then went overseas as a medical registrar to the University Hospital of the West Indies in Kingston Jamaica and Newcastle University Hospital Australia. On returning home I changed career direction and went into General Practice.

On completion of my GP training, and after a few months of GP locums, I went overseas again with Save the Children Fund as a District Medical Officer (DMO) to work in Somalia. My post was originally for six months, but I stayed for two and half years.

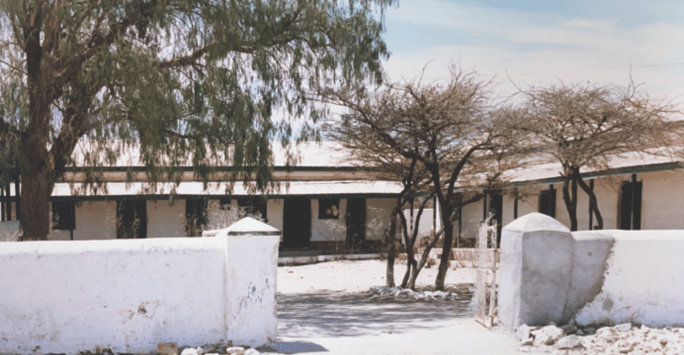

The facade of the hospital in Boroma

The facade of the hospital in Boroma

What took you to Somalia and what did you take from the experience?

The Ethiopian humanitarian crisis and the Live Aid concert in the mid-1980s inspired me to volunteer for Save the Children Fund. However, I was advised to complete my GP training to be more proficient and useful in a third world setting.

Many who work overseas often go out with the intention of helping and providing a service. The truth is, you get as much back as you give, including exposure to another culture and health care system and different diseases.

Examples in Jamaica included sickle cell disease, dengue fever, and a much higher prevalence of severe hypertension, diabetes, and many connective tissue diseases. While in Somalia I dealt with high maternal and child mortality, high prevalence of TB, anaemia, malnutrition and vitamin deficiency, acute and chronic D&V, malaria, snake and spider bites, and limb loss due to land mines.

The post in Somalia was to set up and run a 120-bed sustainable hospital with a small casualty department. The hospital was in very poor condition and had been badly damaged due to an earthquake and bombing by the Ethiopian Air Force.

There were virtually no qualified staff, no lab or other facilities, no medical supplies, no beds or curtains for privacy, and the old pit latrines were full to the brim. When I set off from the UK I did not think that digging latrines was to be one of my first priorities!

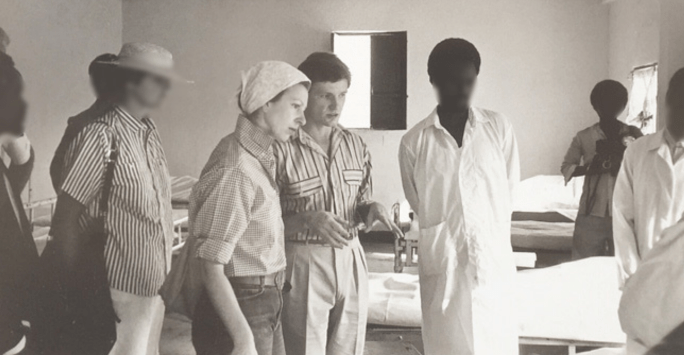

A not-so-welcoming scene on arrival to Somalia

A not-so-welcoming scene on arrival to Somalia

I made lifelong friends and discovered many things about myself, such as how I get great satisfaction from completing tasks and meeting goals and become very dissatisfied with those I am unable to complete. The problem in Somalia was that there was always something more to be done.

What is your new book Noises After Dark all about?

The book details my move to Somalia and how faced with diminishing supplies, poorly trained staff and murmurs of civil unrest, the enormity of the task at hand soon became clear. Recounting both the harrowing and the humorous aspects of living, and working, in a Somali war zone, Noises After Dark really does depict the full spectrum of a community in peril.

Encouraged over many years by family and friends to write my stories, I wanted to share my time in Somalia and raise money for charity in the process, with all profits going to Save the Children.

My inspiration really came from the local characters, many of which were local unsung heroes, who despite all the adversity around them, carried on relentlessly helping their fellow man and community. I dedicate my book to them.

A visit from Princess Anne

A visit from Princess Anne

What advice would you give to a fellow medical professional wishing to do a stint overseas?

If you are considering volunteering or working overseas then think - Why, When, Who, How, What, Where? This is a framework you can apply to any situation in life, and has certainly worked for me.

- Why: Why do you want to do this? What is the motive or goal? What do you want to achieve?

- When: When is the best time for you to do this in your career? For some it may lead to a career pathway working for World Health Organisation (WHO), United Nations (UN), or Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO’s).

- Who: This is very important. Who will you work with? What is the organisation’s reputation? Are they good employers? Will they look after you, especially if you are in danger, or fall ill?

- How: Are they a volunteer organisation or will you get paid? If the latter, can you pay into a pension that is transferable to the NHS on your return to UK? Are you going to work with them alone or with a friend? How long is the contract? Are you well qualified for this type of post, can you do the job needed, or should you undertake further training first?

- What: What are the objectives of the post? What will success look like, and over what time period? Are they achievable?

- Where: Is there somewhere particular you would really like to travel and work? Your destination may sound exciting and exotic, but think twice. If you are offered a post ensure you do your ‘safety homework’. What are the local politics and recent history? Does the UK government recommend travel to this country? What are the potential risks for you, and anyone travelling with you? Is it the sort of place you’d take your children?

How did you get involved with public health work? What are your proudest achievements?

On returning to the UK I made a major change in my life. As a GP, and as a DMO in Somalia, I could see the impact of wider determinants on the population’s health. I decided to retrain as a Consultant in Public Health and worked in this specialty in the East Midlands until I retired.

The government were looking to boost Public Health as a specialty and I explored the new training schemes, opting for a fast-track training post in the East Midlands. I remember being called in by the Director and given a file on my first day. It was a patient who had undergone a hip replacement after suffering a fractured neck of femur and had the wrong hip replaced. ‘Oh and by the way’, said my director as I was leaving the office, ‘the son is a solicitor’.

My proudest moment? It’s difficult to have only one, but for me it is about knowing you have made a difference.

As a clinician in most specialties you have instant feedback from individual patient care. In Public Health you are not the face in front of the patient, but you make a difference in a variety of ways, by changing and influencing the system and standards of care for patients, developing clinical guidelines, care pathways and service standards, and addressing population inequalities in mortality and morbidity.

I’m proud of being involved in the campaign to bring in ‘no smoking in public places’ legislation, which has been instrumental in helping to reduce the prevalence of smoking in the population.

In my area there were 11 local MPs who would be voting on this in Parliament. Initially 9 out of 11 were to vote against this. At the end of our MP lobbying and marketing campaign 10 out of 11 voted for the new law. At medical school I never thought that one of the most important things I would do as a doctor, would be campaigning and visiting MPs.

What advice do you have for student doctors interested in Public Health?

- Look up and understand Public Health concepts of health and wider determinants of health and take these into account during other clinical placements so that you have a more holistic view of your patients.

- Consider a Public Health based course or placement when you select an intercalation year. The knowledge and skills you learn will be useful regardless of whichever speciality you choose in future.

- Meet junior or senior colleagues in Public Health and shadow them if you can. Ask them to go through their work diaries to explore an average month’s work.

- As with any specialty, take time to do your homework. Public Health has long-term goals that replace short-term patient interactions. This can take some time to come to terms with, as everything can seem very slow at first. The work can be quite varied and changeable. You need to like change to work in Public Health! It is also often at the interface between clinical care and politics, you will need to learn to work the system.

John Tomlinson

John Tomlinson

What advice would you have for yourself as a student doctor?

Enjoy yourself! There is so much specialty career choice, and a job is almost certain at the end.

Seek and take up opportunities when they are available, you might never get the chance again.

Making the right career choice isn’t easy, and it’s normal not to know what you want to do once you have qualified. Don’t feel rushed into making a specialty choice if you are unsure. Although it may not seem like it, time is on your side.

Meet people in different specialties to understand what it’s really like. If you are not sure, try and get experience in general underpinning specialties initially, as they will be useful whatever you do in future.

- Noises After Dark is available in paperback and e-book through the Troubadour publisher website and all good bookshops and online outlets.

- Profits from the book will go to Save the Children Fund. The proportion raised for charity varies depending on the point of sale. For paperbacks the differences can be large, with sales through Troubador generating more money for charity.

- Keen to explore more tales from Liverpool graduates? Head to our Alumni Stories catalogue.